How earthquake scientists eavesdrop on North Korea’s nuclear blasts

On September 9 of last year, in the middle of the morning, seismometers began lighting up around East Asia. From South Korea to Russia to Japan, geophysical instruments recorded squiggles as seismic waves passed through and shook the ground. It looked as if an earthquake with a magnitude of 5.2 had just happened. But the ground shaking had originated at North Korea’s nuclear weapons test site.

It was the fifth confirmed nuclear test in North Korea, and it opened the latest chapter in a long-running geologic detective story. Like a police examiner scrutinizing skid marks to figure out who was at fault in a car crash, researchers analyze seismic waves to determine if they come from a natural earthquake or an artificial explosion. If the latter, then scientists can also tease out details such as whether the blast was nuclear and how big it was. Test after test, seismologists are improving their understanding of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program.

The work feeds into international efforts to monitor the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, which since 1996 has banned nuclear weapons testing. More than 180 countries have signed the treaty. But 44 countries that hold nuclear technology must both sign and ratify the treaty for it to have the force of law. Eight, including the United States and North Korea, have not.

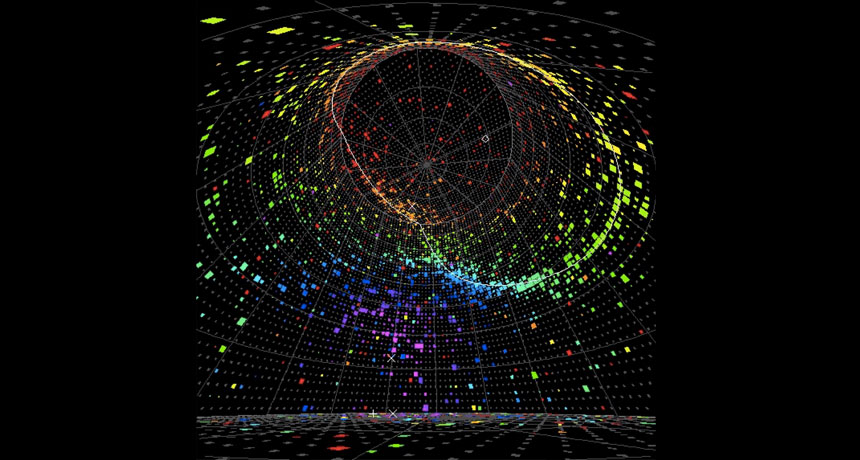

To track potential violations, the treaty calls for a four-pronged international monitoring system, which is currently about 90 percent complete. Hydroacoustic stations can detect sound waves from underwater explosions. Infrasound stations listen for low-frequency sound waves rumbling through the atmosphere. Radionuclide stations sniff the air for the radioactive by-products of an atmospheric test. And seismic stations pick up the ground shaking, which is usually the fastest and most reliable method for confirming an underground explosion.

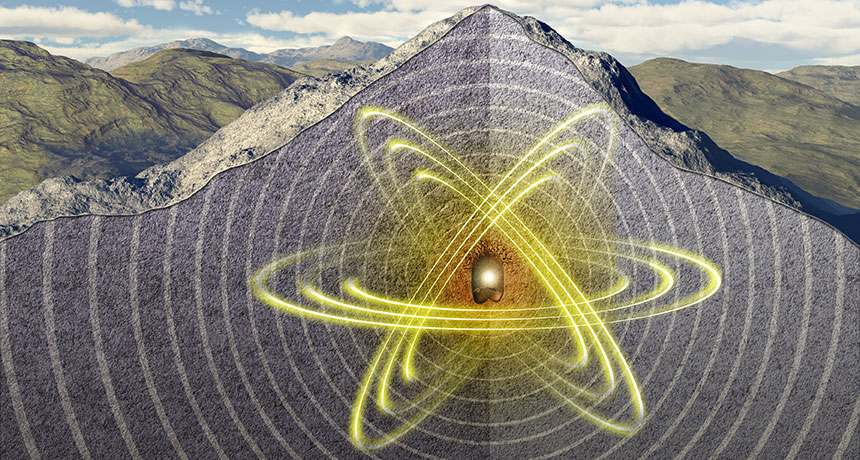

Seismic waves offer extra information about an explosion, new studies show. One research group is exploring how local topography, like the rugged mountain where the North Korean government conducts its tests, puts its imprint on the seismic signals. Knowing that, scientists can better pinpoint where the explosions are happening within the mountain — thus improving understanding of how deep and powerful the blasts are. A deep explosion is more likely to mask the power of the bomb.

Separately, physicists have conducted an unprecedented set of six explosions at the U.S. nuclear test site in Nevada. The aim was to mimic the physics of a nuclear explosion by detonating chemical explosives and watching how the seismic waves radiate outward. It’s like a miniature, nonnuclear version of a nuclear weapons test. Already, the scientists have made some key discoveries, such as understanding how a deeply buried blast shows up in the seismic detectors.

The more researchers can learn about the seismic calling card of each blast, the more they can understand international developments. That’s particularly true for North Korea, where leaders have been ramping up the pace of military testing since the first nuclear detonation in 2006. On July 4, the country launched its first confirmed ballistic missile — with no nuclear payload — that could reach as far as Alaska.

“There’s this building of knowledge that helps you understand the capabilities of a country like North Korea,” says Delaine Reiter, a geophysicist with Weston Geophysical Corp. in Lexington, Mass. “They’re not shy about broadcasting their testing, but they claim things Western scientists aren’t sure about. Was it as big as they claimed? We’re really interested in understanding that.”

Natural or not

Seismometers detect ground shaking from all sorts of events. In a typical year, anywhere from 1,200 to 2,200 earthquakes of magnitude 5 and greater set off the machines worldwide. On top of that is the unnatural shaking: from quarry blasts, mine collapses and other causes. The art of using seismic waves to tell one type of event from the others is known as forensic seismology.

Forensic seismologists work to distinguish a natural earthquake from what could be a clandestine nuclear test. In March 2003, for instance, seismometers detected a disturbance coming from near Lop Nor, a dried-up lake in western China that the Chinese government, which signed but hasn’t ratified the test ban treaty, has used for nuclear tests. Seismologists needed to figure out immediately what had happened.

One test for telling the difference between an earthquake and an explosion is how deep it is. Anything deeper than about 10 kilometers is almost certain to be natural. In the case of Lop Nor, the source of the waves seemed to be located about six kilometers down — difficult to tunnel to, but not impossible. Researchers also used a second test, which compares the amplitudes of two different kinds of seismic waves.

Earthquakes and explosions generate several types of seismic waves, starting with P, or primary, waves. These waves are the first to arrive at a distant station. Next come S, or secondary, waves, which travel through the ground in a shearing motion, taking longer to arrive. Finally come waves that ripple across the surface, including those called Rayleigh waves.

In an explosion as compared with an earthquake, the amplitudes of Rayleigh waves are smaller than those of the P waves. By looking at those two types of waves, scientists determined the Lop Nor incident was a natural earthquake, not a secretive explosion. (Seismology cannot reveal the entire picture. Had the Lop Nor event actually been an explosion, researchers would have needed data from the radionuclide monitoring network to confirm the blast came from nuclear and not chemical explosives.)

For North Korea, the question is not so much whether the government is setting off nuclear tests, but how powerful and destructive those blasts might be. In 2003, the country withdrew from the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, an international agreement distinct from the testing ban that aims to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and related technology. Three years later, North Korea announced it had conducted an underground nuclear test in Mount Mantap at a site called Punggye-ri, in the northeastern part of the country. It was the first nuclear weapons test since India and Pakistan each set one off in 1998.

By analyzing seismic wave data from monitoring stations around the region, seismologists concluded the North Korean blast had come from shallow depths, no more than a few kilometers within the mountain. That supported the North Korean government’s claim of an intentional test. Two weeks later, a radionuclide monitoring station in Yellowknife, Canada, detected increases in radioactive xenon, which presumably had leaked out of the underground test site and drifted eastward. The blast was nuclear.

But the 2006 test raised fresh questions for seismologists. The ratio of amplitudes of the Rayleigh and P waves was not as distinctive as it usually is for an explosion. And other aspects of the seismic signature were also not as clear-cut as scientists had expected.

Researchers got some answers as North Korea’s testing continued. In 2009, 2013 and twice in 2016, the government set off more underground nuclear explosions at Punggye-ri. Each time, researchers outside the country compared the seismic data with the record of past nuclear blasts. Automated computer programs “compare the wiggles you see on the screen ripple for ripple,” says Steven Gibbons, a seismologist with the NORSAR monitoring organization in Kjeller, Norway. When the patterns match, scientists know it is another test. “A seismic signal generated by an explosion is like a fingerprint for that particular region,” he says.

With each test, researchers learned more about North Korea’s capabilities. By analyzing the magnitude of the ground shaking, experts could roughly calculate the power of each test. The 2006 explosion was relatively small, releasing energy equivalent to about 1,000 tons of TNT — a fraction of the 15-kiloton bomb dropped by the United States on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945. But the yield of North Korea’s nuclear tests crept up each time, and the most recent test, in September 2016, may have exceeded the size of the Hiroshima bomb.

Digging deep

For an event of a particular seismic magnitude, the deeper the explosion, the more energetic the blast. A shallow, less energetic test can look a lot like a deeply buried, powerful blast. Scientists need to figure out precisely where each explosion occurred.

Mount Mantap is a rugged granite mountain with geology that complicates the physics of how seismic waves spread. Western experts do not know exactly how the nuclear bombs are placed inside the mountain before being detonated. But satellite imagery shows activity that looks like tunnels being dug into the mountainside. The tunnels could be dug two ways: straight into the granite or spiraled around in a fishhook pattern to collapse and seal the site after a test, Frank Pabian, a nonproliferation expert at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, said in April in Denver at a meeting of the Seismological Society of America.

Researchers have been trying to figure out the relative locations of each of the five tests. By comparing the amplitudes of the P, S and Rayleigh waves, and calculating how long each would have taken to travel through the ground, researchers can plot the likely sites of the five blasts. That allows them to better tie the explosions to the infrastructure on the surface, like the tunnels spotted in satellite imagery.

One big puzzle arose after the 2009 test. Analyzing the times that seismic waves arrived at various measuring stations, one group calculated that the test occurred 2.2 kilometers west of the first blast. Another scientist found it only 1.8 kilometers away. The difference may not sound like a lot, Gibbons says, but it “is huge if you’re trying to place these relative locations within the terrain.” Move a couple of hundred meters to the east or west, and the explosion could have happened beneath a valley as opposed to a ridge — radically changing the depth estimates, along with estimates of the blast’s power.

Gibbons and colleagues think they may be able to reconcile these different location estimates. The answer lies in which station the seismic data come from. Studies that rely on data from stations within about 1,500 kilometers of Punggye-ri — as in eastern China — tend to estimate bigger distances between the locations of the five tests when compared with studies that use data from more distant seismic stations in Europe and elsewhere. Seismic waves must be leaving the test site in a more complicated way than scientists had thought, or else all the measurements would agree.

When Gibbons’ team corrected for the varying distances of the seismic data, the scientists came up with a distance of 1.9 kilometers between the 2006 and 2009 blasts. The team also pinpointed the other explosions as well. The September 2016 test turned out to be almost directly beneath the 2,205-meter summit of Mount Mantap, the group reported in January in Geophysical Journal International. That means the blast was, indeed, deeply buried and hence probably at least as powerful as the Hiroshima bomb for it to register as a magnitude 5.2 earthquake.

Other seismologists have been squeezing information out of the seismic data in a different way — not in how far the signals are from the test blast, but what they traveled through before being detected. Reiter and Seung-Hoon Yoo, also of Weston Geophysical, recently analyzed data from two seismic stations, one 370 kilometers to the north in China and the other 306 kilometers to the south in South Korea.

The scientists scrutinized the moments when the seismic waves arrived at the stations, in the first second of the initial P waves, and found slight differences between the wiggles recorded in China and South Korea, Reiter reported at the Denver conference. Those in the north showed a more energetic pulse rising from the wiggles in the first second; the southern seismic records did not. Reiter and Yoo think this pattern represents an imprint of the topography at Mount Mantap.

“One side of the mountain is much steeper,” Reiter explains. “The station in China was sampling the signal coming through the steep side of the mountain, while the southern station was seeing the more shallowly dipping face.” This difference may also help explain why data from seismic stations spanning the breadth of Japan show a slight difference from north to south. Those differences may reflect the changing topography as the seismic waves exited Mount Mantap during the test.

Learning from simulations

But there is only so much scientists can do to understand explosions they can’t get near. That’s where the test blasts in Nevada come in.

The tests were part of phase one of the Source Physics Experiment, a $40-million project run by the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration. The goal was to set off a series of chemical explosions of different sizes and at different depths in the same borehole and then record the seismic signals on a battery of instruments. The detonations took place at the nuclear test site in southern Nevada, where between 1951 and 1992 the U.S. government set off 828 underground nuclear tests and 100 atmospheric ones, whose mushroom clouds were seen from Las Vegas, 100 kilometers away.

For the Source Physics Experiment, six chemical explosions were set off between 2011 and 2016, ranging up to 5,000 kilograms of TNT equivalent and down to 87 meters deep. The biggest required high-energy–density explosives packed into a cylinder nearly a meter across and 6.7 meters long, says Beth Dzenitis, an engineer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California who oversaw part of the field campaign. Yet for all that firepower, the detonation barely registered on anything other than the instruments peppering the ground. “I wish I could tell you all these cool fireworks go off, but you don’t even know it’s happening,” she says.

The explosives were set inside granite rock, a material very similar to the granite at Mount Mantap. So the seismic waves racing outward behaved very much as they might at the North Korean nuclear test site, says William Walter, head of geophysical monitoring at Livermore. The underlying physics, describing how seismic energy travels through the ground, is virtually the same for both chemical and nuclear blasts.

The results revealed flaws in the models that researchers have been using for decades to describe how seismic waves travel outward from explosions. These models were developed to describe how the P waves compress rock as they propagate from large nuclear blasts like those set off starting in the 1950s by the United States and the Soviet Union. “That worked very well in the days when the tests were large,” Walter says. But for much smaller blasts, like those North Korea has been detonating, “the models didn’t work that well at all.”

Walter and Livermore colleague Sean Ford have started to develop new models that better capture the physics involved in small explosions. Those models should be able to describe the depth and energy release of North Korea’s tests more accurately, Walter reported at the Denver meeting.

A second phase of the Source Physics Experiment is set to begin next year at the test site, in a much more rubbly type of rock called alluvium. Scientists will use that series of tests to see how seismic waves are affected when they travel through fragmented rock as opposed to more coherent granite. That information could be useful if North Korea begins testing in another location, or if another country detonates an atomic bomb in fragmented rock.

For now, the world’s seismologists continue to watch and wait, to see what the North Korean government might do next. Some experts think the next nuclear test will come at a different location within Mount Mantap, to the south of the most recent tests. If so, that will provide a fresh challenge to the researchers waiting to unravel the story the seismic waves will tell.

“It’s a little creepy what we do,” Reiter admits. “We wait for these explosions to happen, and then we race each other to find the location, see how big it was, that kind of thing. But it has really given us a good look as to how [North Korea’s] nuclear program is progressing.” Useful information as the world’s nations decide what to do about North Korea’s rogue testing.