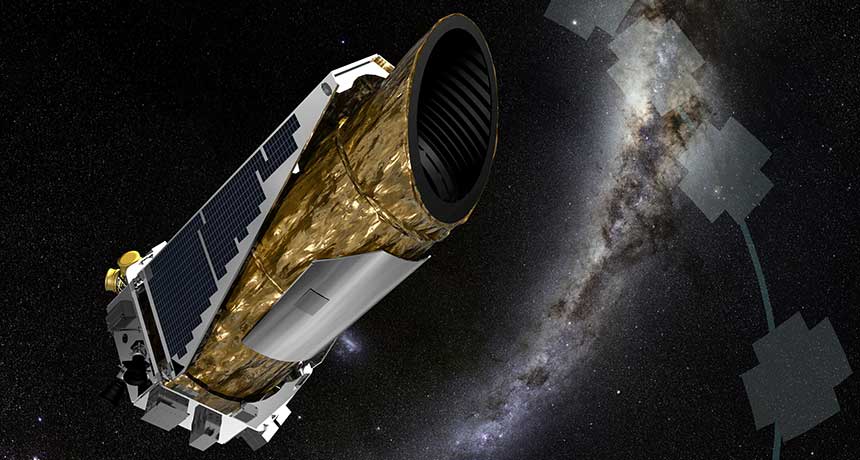

Kepler telescope readies for new mission after communications scare

The Kepler space telescope, NASA’s premier planet hunter, is about to embark on a hunt for planets toward the center of the galaxy. But on April 7, just hours before its new mission was set to begin, the observatory gave astronomers a scare by temporarily hunkering down in an emergency state that prevented mission controllers from communicating with the spacecraft. As of April 11, though, Kepler was talking to Earth again, and engineers are getting the telescope prepped for its new quest.

“A cause has not been determined; that will take time,” says NASA spokesperson Michelle Johnson. “The priority is returning the spacecraft to science mode.”

Kepler has previously had problems with its reaction wheels, which are necessary for keeping the spacecraft pointed in the right direction. After two of its wheels stopped working, the telescope took a break from planet hunting in 2013. Engineers at Ball Aerospace figured out how to get Kepler working again with the two remaining wheels by using pressure from sunlight to balance the telescope. While engineers don’t yet know why Kepler shut down this time, early reports indicate that the remaining reaction wheels are not to blame.

Once the spacecraft checks out, Kepler will kick off its latest effort, looking toward the galactic center for planets whose gravity distorts the light from far more distant stars. This technique, known as gravitational microlensing, has been used with ground-based telescopes to discover about 46 planets, some of them orphaned from their parent stars. But the method is a first for Kepler, which searches for dips in starlight caused by planets crossing in front of their suns.

This phase of Kepler’s mission will last until July 1. Even if it doesn’t turn up any new exoplanets, it’s guaranteed to see at least one world: To look at the center of the galaxy, Kepler has to point toward Earth. The telescope that has spent over half a decade searching for other worlds will snap a picture of our planet that will be released later this year.