Rogue antibody linked to severe second dengue infections

The playground ditty “first the worst, second the best” isn’t always true when it comes to dengue fever. Some patients who contract the virus a second time can experience more severe symptoms. A rogue type of antibody may be to blame, researchers report in the Jan. 27 Science. Instead of protecting their host, the antibodies are commandeered by the dengue virus to help it spread, increasing the severity of the disease.

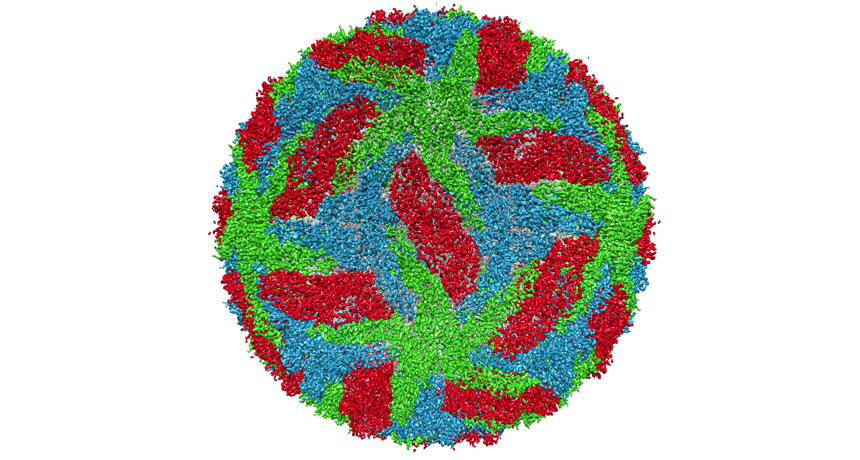

Four closely related viruses cause dengue, a mosquito-transmitted disease marked by fever, muscle pain and other flulike symptoms. When a previously infected person contracts a second type of dengue, leftover antibodies can react with the new virus.

Fewer than 15 percent of people with a second infection develop severe dengue disease. Those who do may produce a different type of antibody, says Taia Wang, an infectious diseases researcher with the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Wang and colleagues found that dengue patients with a dangerously low blood platelet count — a sign of severe dengue disease — had an abundance of these variant antibodies.

Tests in mice supported the connection. “We found that when we transferred the antibodies from patients with severe disease into mice, they triggered platelet loss,” Wang says.

Wang says it’s not known why some people have this alternate antibody. She and her team want to determine that, along with how these antibodies are regulated by the immune system. With further research, they may be able to screen people to identify those more susceptible to severe dengue disease, Wang says.

Anna Durbin, a dengue vaccine researcher at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, doesn’t see a strong connection between this type of antibody and the severity of dengue disease. But she says that the research was interesting in how it connected dengue to low platelet count, a condition known as thrombocytopenia.

“There’s a lot of different theories out there about the role of dengue antibodies and thrombocytopenia, and whether or not the virus itself can enter platelets,” Durbin says. “I think this paper may provide more insight into what is the pathogenic mechanism of thrombocytopenia and dengue, and raises some good avenues for further research.”